Dr Manel Herat is a Senior Lecturer in English Language at Liverpool Hope University. And here in this article, which forms part of our 'Expert Comment' series, Dr Herat considers the treatment of refugees - and the language used by the media and other officials to talk about those fleeing war in Ukraine.

In the Refugee Dictionary, compiled by @UNRefugeesUK, which has hundreds of entries, Mairi from Edinburgh defines a refugee as a “a friend, a brother or sister to wrap your arms around and say let me help you, let me share your burden, you have a future and you too deserve to live in peace, to give your children a positive future, to eat and sleep in safety.” (Mairi/Edinburgh)

Since the 24 th of February, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian citizens have been displaced and made homeless due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This has led to Ukrainians having to flee their homes to find refuge in neighbouring countries. The Indian TV Programme, Gravitas (WION, India), has accused the Western Media and other European politicians and journalists of focusing on race and skin colour and foregrounding white supremacy in talking about the Ukrainian refugees instead of seeing their plight. This report suggests that Europeans typically imagine refugees as being coloured and coming from poor, under-developed countries and find it horrifying to see refugees from Europe who are white.

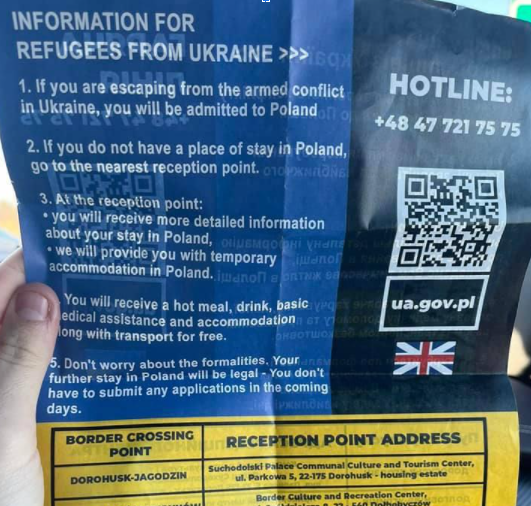

Over the last two weeks, excluding Britain, other European nations such as Poland, have opened their borders to the hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing Ukraine, and giving them shelter and safety. In the media there have been images of mothers leaving strollers for refugee women coming into Poland with babies. The open arms welcome that Poland has given Ukrainian refugees highlights that there was no material or resource problem for the Polish government to receive refugees fleeing from other countries such as Syria and Afghanistan. The following leaflet (from Mac McKenna/Facebook) shows the English language version (Ukrainian on other side) of the information given to new arrivals at the Polish border crossing:

“You will receive a hot meal, drink and accommodation…don’t worry about the formalities. Your

further stay in Poland will be legal. You don’t have to submit any applications in the coming days”,

According to a commentator, “this is what everyone should get at every border should they be uprooted and need to move” (K. Ovendon/Facebook). The flexibility demonstrated here by European countries in welcoming refugees and making their residence easier, is noticeably in marked contrast to the treatment bestowed on Syrian and North African refugees, who were fleeing previous violent conflicts even more severe than the Russian-Ukrainian war, when there was much hostility from some European countries to accepting refugees.

Reports on the refugee crisis (reliefweb.int) have also suggested discriminatory behaviour on the part of Europeans to refugees of black or brown skin colour. Students and Ukrainians of colour from African and Arabic countries interviewed on TV have recounted the hardships they had to undergo at the Polish border, where they had to wait for hours without any assistance, and how some of them, particularly those with dark skin, were denied entry for no apparent reason and were stranded at the border.

White Ukrainians, on the other hand, were given special treatment, such as the ability to cross the border without a visa and travel by train without purchasing a ticket. Indians residing in Ukraine have also said that in fleeing the country, white Ukrainians were given first preference in crossing the border, whereas they were not allowed to board the trains and had a hard time trying to get across (reliefweb.org). In the Independent UK (11.03.2022), a Nigerian man from Ukraine, said that ‘nobody [was] talking’ to black refugees and that they were shipped far away from

other refugees.

Apart from the discriminatory behaviour illustrated by European countries, Gravitas also accused European journalists and media outlets of using a racist discourse, focusing on the fact that Ukrainian refugees are ‘civilized’, in comparison to refugees from the Middle East and North Africa, who are perceived as ‘uncivilized’ and labelled terrorists. In analysing racist discourse, Teun Van Dijk argues that in biased portrayals of facts in favour of the speaker's or writer's own interests, the general technique of ‘positive self-presentation’ and ‘negative other presentation’ is highly frequent

and that the normal tendency is to blame unfavourable situations and occurrences on opponents or on the Others (2006:373). This is evidenced in a clip mentioned by Gravitas, which shows the language used by CBS's foreign correspondent Charlie D'Agata, where he expresses his horror at how such a conflict could happen to a “civilised” nation. He says: "This isn't a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for

decades... This is a relatively civilized, relatively European --- I have to choose those words carefully,

too --- city, where you wouldn't expect that or hope that it's going to happen."

The words ‘civilised’ and ‘European’ stand in opposition to ‘uncivilised’ and ‘non-European projecting what Edward Said (1978) has noted as Western superiority over Eastern cultures manifested through discourse that enables Europeans to be perceived as more superior and advanced in comparison to Orientals.

Despite the fact that the correspondent has apologised following considerable criticism on social media, his comments represent the thoughts and feelings of a huge number of journalists who commented about the issue using similar language dichotomies: NBC Reporter from the US says “These are not refugees from Syria, these are Christians, they are white, they are very similar to us.”

Likewise, an ITV Correspondent from Britain reporting from Poland said: "This is not a developing

third world nation. This is Europe."

Meanwhile, a journalist from BFM in France said on live TV: "We're not talking here about Syrians fleeing the bombing of the Syrian regime backed by Putin, we're talking about Europeans leaving in cars that look like ours to save their lives." Peter Dobbie, a reporter from Al Jazeera also remarked on the difference between Ukrainian

refugees and refugees from the Middle East and North Africa, talking about how ‘prosperous’ the Ukrainians are in comparison to the other. He says: "What is compelling is that just looking at them the way they're dressed. These are prosperous, middle-class people. These are not obviously refugees trying to get away from areas in the Middle East that are still in a big state of war. These are not people trying to get away from areas in North Africa. They look like any European family that you would live next door to."

Discriminatory language was also evident from people other than journalists. The BBC hosted the former Ukrainian Deputy Prosecutor, David Sakvarelidze, who said: "It's very emotional for me because I see European people with blue eyes and blonde hair being killed, children being killed every day by Putin's missiles, helicopters, and rockets."

Echoes of a similar vein are also noticeable at the top levels of government, for example, the Bulgarian Prime Minister Kiril Petkov said: "These people are intelligent, they are educated people.... This is not the refugee wave we have been used to, people we were not sure about their identity, people with unclear pasts, who could have been even terrorists."

The language used by media and other officials discussed above point to the tendency to see ‘whiteness’ as superior to others in intelligence, education and character. This highlights the opposition between ‘them’ and ‘us’, confirming that discourses of otherness generally take a negative perception of the other (Said, 1978, Van Dijk, 2006). Here, the identity of ‘others’ – refugees from Middle East and North Africa, is widely perceived as being unintelligent, uneducated

and untrustworthy, coming from ‘uncivilised’ parts of the world. These responses to the Ukraine refugee crisis therefore have exposed the racism and discrimination that excludes and stigmatises non-white, non-Christian refugees.

As the definition of refugee given at the beginning of this paper shows, all refugees, whatever ethnicity, skin colour or religion, deserve compassion and this is highlighted in the following poem by

Brian Bilston:

They have no need of our help

So do not tell me

These haggard faces could belong to you or me

Should life have dealt a different hand

We need to see them for who they really are

Chancers and scroungers

Layabouts and loungers

With bombs up their sleeves

Cut-throats and thieves

They are not

Welcome here

We should make them

Go back to where they came from

They cannot

Share our food

Share our homes

Share our countries

Instead let us

Build a wall to keep them out

It is not okay to say

These are people just like us

A place should only belong to those who are born there

Do not be so stupid to think that

The world can be looked at another way

(now read from bottom to top)